Interview with Daniel Handler, aka Lemony Snicket

"The spookiest and most delightful thing in the world"

Author’s note: Over the coming months, I plan to run interviews with current practitioners of Jewish horror. I’m delighted to share the first of these, a Q&A with the unyieldingly inspiring Daniel Handler, aka Lemony Snicket.

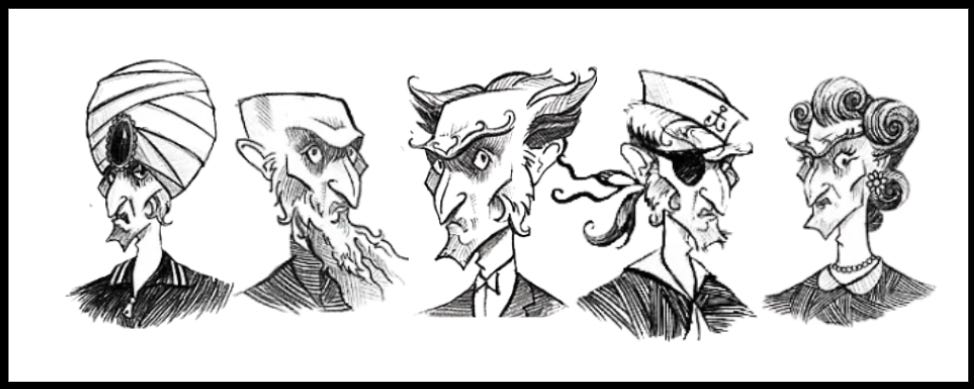

For the majority of my life, Lemony Snicket has been one of my favorite writers. I came of age around the turn of the millennium, just as he was dropping his hyper-literary and ambience-soaked A Series of Unfortunate Events. Growing up in lockstep with these books really got to me, especially the early ones, where he refined a sitcom-like setup in which the main characters, a trio of rich orphans, find themselves in the care of one hapless adult after another, all while the nefarious (and genuinely terrifying) Count Olaf shows up in disguise, his many eyes (he had more than two) engorging at the thought of their fortune.

But it wasn’t just the characters and plots and most of all the words that had me hooked — as if by a handless henchman, I should say. There was something about the identity of the writer that was so unusual and unique. To that point, as a reader of age-appropriate fiction, I was familiar with an endless glut of double-initialed first name authors who wrote stories, some good, some bad, and left it there. Never did they appear in the text as characters or, as those characters, never did they present secondary narratives around the margins of the main one. Put differently, never before had they made the process of writing a central part of the story. This was new, it was big, and it gave me and my friends much fodder to build out our budding Baudelaire fandom.

As an adult revisiting the books, I was struck by how hilarious they remain, and by how much the author was able to get away with. The chapters of Lemony Snicket’s unfortunate series are filled with kidnapping, child imprisonment, murder (of adults), attempted murder (of children), child labor, suicide by leech, shooting children with harpoon guns, letting children die of poison, and perhaps most disquieting, the constant, recurring idea of waiting for a child to turn 18 in order to “gain access” to them, though in this case the motivation is purely monetary.

And then there’s the matter of Brett Helquist’s cover illustration for the fifth book in the series, which has properly haunted me since the moment I purchased it in August 2000 at the Barnes & Noble on Broadway and West 82nd Street.

This book, by the way, is historic for introducing the word “cakesniffers” to the English lexicon, an insult I’ve employed many times to varying effect.

Like most writers, I’m hesitant to over-analyze the influences on my work, but I see The Writer From San Francisco’s inspiration all over the wordplay and doomed atmospherics of Gershom’s Golem (about a mystical response to rising antisemitism), the unreliable adults and their sinister plans in Savta’s Claws (about a Jewish grandmother who employs tree-tethered voodoo to heal and harm), or the dark academic logophilia of Studies in Idolatry (an introduction to a book that doesn’t exist about modern day cults inspired by Biblical-era worship).

I love to write, and every day of my life that I’ve liked enough to hang up and admire has included some measure of writing in it. If I had to, I could probably pinpoint eight writers who sparked the fire of what I’m trying to do with my own work, and Daniel Handler, in his brilliant citrusy disguise, is the tall man towering at the center of the frame.

When I reached out to him last month, he was kind enough to answer a few questions. Our exchange is below.

INTERVIEW WITH DANIEL HANDLER

I’d love to ask about your general approach to writing. Most of the fiction writers I know (myself included) break their process down into four categories: inspiration, pre-writing, drafting, and editing. These seem to be common steps for taking an idea and turning it into a prose piece that others can enjoy. Does this reflect your process? Are there other methods you use? Or do you approach writing differently altogether?

DANIEL HANDLER: I think the writer Michelle Tea puts it best, in that it's like preschool: you have to make a mess, and then you have to clean up. I have a messy period, of vague ideas, peculiar research, rereading books that seem relevant, notes that end up on index cards getting organized and re-organized, and it all goes into a big ugly first draft in which anything is possible. Then I clean it all up: I figure out what the piece is really about, I do whatever research I missed the first time around, I get merciless with what gets discarded, I sharpen up the sentences, and then I have a really terrible second draft. I do a few more rounds of this and then maybe I have something.

Do you have any specific rituals around writing? For example, I like writing in front of a window with a view, while music plays from behind me. This feels important to my craft — having a visual in front of me (currently Lexington Avenue) and sound emerging from behind (currently The Magnetic Fields). Do you have similar writing rituals? Specific places you write? Do you listen to music while working, or do you need complete quiet?

DANIEL HANDLER: I work mostly in cafés and libraries, writing by hand on legal pads, and I usually have headphones on, some kind of wordless, somewhat ambient music to blot out the chatter around me. My rituals used to be more specific--I made many playlists back in the day--but there can be a fine line between a ritual and an excuse to not put ink on paper. I aim to be as portable and flexible as possible.

I’ve been a huge fan of yours for two thirds of my existence, but you came on my radar recently because of a Deadline article that you’re working on a screenplay about a golem. Can you share any updates on the project? Also, I’d love to hear about your approach to screenwriting. How does it differ from writing a novel or short story? What factors do you consider when writing for the screen, where words are blueprints rather than the final product?

DANIEL HANDLER: Movies are expensive to make--much, much more expensive than a novel, in which the sentences "They stopped at a diner and ate sandwiches" and "They stopped by the side of a lake and watched the serpent strangling the nurse" cost the same amount of money. Thus, screenplays have to sell themselves at every turn, to the people reading them--the actors, the directors, the people in charge of the money and the people who might fire everyone. I think I have a grasp on how film works, but not so much on the interminable self-selling of the movie business, which is a long way of saying the golem movie has another writer now.

Golems are often considered the quintessential Jewish monster and are certainly the most prominent in Jewish horror cinema. The most popular version of the legend is centered on the Maharal of Prague and emerges from a deeply defensive posture, one of protection born out of desperation. The Jews are so powerless, their only possible savior is animated clay. Does the golem have personal symbolism for you? Are there specific sources or texts of Jewish mysticism you consult before writing about one?

DANIEL HANDLER: The golem asks so many exciting questions--about security and vengeance, about what precisely we mean by life--and answers them in silence, which is a pretty good trick. I've traipsed through assorted mystic texts in and out of the Jewish tradition, lifting whatever details struck me.

Has your approach to writing about the golem changed since your second book, Watch Your Mouth? Did Rabbi Tsouris make it into the screenplay?

DANIEL HANDLER: Those are different golems, I think--Watch Your Mouth is about the myths we project onto our own families, and the movie was more about anti-Semitism. I had a rabbinical campus chaplain in my draft, but I'm grateful anyone remembers Rabbi Tsouris.

My newsletter, Hebrew Horror, explores scary stories rooted in Jewish themes, and I absolutely consider the Baudelaires’ tale to be foundational Jewish horror. There’s something deeply Semitic (in the spookiest sense) about your bookish, inventive, and sharp-tongued trio: essentially, a family in perpetual exile, wandering from home to home after being banished by a fiery destruction. Similarly, one of my favorite villains in all of literature is Count Olaf, who I’ve always seen as a perfect stand-in for the shayd, a shapeshifting demon from Jewish folklore that longs to be human and can change any part of its body except for its chicken-like feet. That’s Olaf to me in the early books: constantly in disguise, but always betrayed by a giveaway spooky tell, often involving his feet. Were you familiar with the shayd when developing his character? Were there other inspirations in shaping a character so adept at camouflage?

DANIEL HANDLER: Oh, I do like a shayd. I've circled the idea of a shape-shifter for a long time, and I'm gratified at your offer that maybe in Count Olaf I managed to ink the idea after all. I always thought the Baudelaires' story was a Jewish one, although for me Olaf was always the unsavory truths about life, that children see spot-on but adults have learned to conveniently ignore. But yes, a shayd, I can see that too. (To veer a bit, I recently saw a new shapeshifting movie, Head Count, which I thought was terrific.)

When I tell people I write Jewish horror, the response is almost always the same joke: “You mean you write history?” The idea that real-life atrocities somehow disqualify us from engaging with fictional monsters is absurd. Jewish tradition, literature, and lore spans a vast canon overflowing with concepts and creatures that are terrifying, mystical, and wildly underexplored. Why do you think so few writers have tapped into this rich terrain?

DANIEL HANDLER: If it's a vast canon, so surely lots of writers have tapped into it, yes? I do agree that we've been in a lackluster cultural moment of plodding literalism, in which we are all encouraged to think about the world without metaphor or irony. (And how's that going, by the way?) I like to think of all the creepy creatures doing what creepy creatures do--lurking someplace, where few people can see that they're doing so much more than any innocent citizen suspects.

Some of the scenarios in A Series of Unfortunate Events you create are so unsettling. For me, the scariest of the Baudelaire books is The Ersatz Elevator. Because of one specific fright. The idea of living in a penthouse so massive that your enemy could be hiding in a room you’ve never entered — or under a couch in your fourth living room or behind the east bookshelf in the south library — still unnerves me. Have you ever experienced something truly frightening or unexplainable? A ghost? A moment that defied reason and stuck with you?

DANIEL HANDLER: I hate to duck a question by hawking a book, but my recent memoir And Then, And Then, What Else? chronicles some hauntings that began for me in late adolescence and continue to this day. But yes, I see things.

Growing up in the late 1990s, I devoured age-appropriate horror from authors like R.L. Stine, Alvin Schwartz, K.A. Applegate, Louis Sachar, Paul Jennings, Roald Dahl, and of course, you. I re-read many of these books as an adult while working on my children’s horror podcast and I found few held up in terms of scare factor or story quality. Most felt formulaic and with even the smallest glance, I could see the writer writing them. But you and Dahl were as creepy and original to me at 35 as at 11. I think it’s partly because you both villainize adults as the main adversary of children. Count Olaf was especially terrifying because he represents a very real, very scary threat to the Baudelaire kids that no other adults in their life could even recognize. (Except for Justice Strauss, and her ending is so dark I still don’t know how you got away with that). This, I believe, is the scariest thing about childhood: grown-ups who are meant to protect us doing us the most harm. Are there concepts in horror that are especially frightening to you? Either when you were a child or now?

DANIEL HANDLER: I think the scariest thing is the unseen--which is why so much horror falls apart in the last bit, when the monster is there in all its rubber tentacles and stage blood. Beforehand, the dread and suspense--that's the juicy bit. A hand moving in a way you fail to recognize, someone's voice stuttering into the wrong pitch, a noise at the window that just doesn't sound right. This is what frightened me when I was very young--I saw Philp Kaufman's Invasion of the Body Snatchers at a tender age--and what frightens me now.

Have you ever gotten that eerie feeling of encountering something in the world that you wrote? As if by writing it, you birthed it into existence?

This question needs some background. In 2002, my best friend Josh and I were obsessed with your books and the idea of your pseudonym. At the time, there was a general conversation among young readers around the country about who the real Lemony Snicket was. Slight trickster that I am, I convinced Josh that my uncle, a rabbi in a synagogue of the Upper West Side of Manhattan, was Lemony Snicket. It made sense because my secretive uncle was a great storyteller and schmoozer, and also a lawyer (this was “evidence” I used to convince Josh, with my VFD-addled brain, that “Series of Unfortunate Events” was actually an anagram for SUE, i.e. Lemony Snicket telling us in code that he’s a litigious lawyer). The following year, my uncle got married, and Josh pestered me to attend the wedding. My mom said he could come but only if I told him the truth, that Lemony Snicket was not my uncle. I agreed, grumbling, and told Josh. He took it well and we had a ball at the chuppah. Except for a moment at the smorgasbord. Josh and I were on line, waiting for the server to slice us some corned beef, when he elbowed me, eyes wide, and pointed to the next table over. Two servers stood at it, towering over piles of sushi. They looked like twins, in their forties, and both had white powder all over their faces. Josh and I stared as they smiled at us and it felt like the world cracked open.

Have you ever encountered something from your writing in the real world? I don’t mean fans dressing as characters, or themed readings, or ankle tattoos of eyes. I mean: have you, unrecognized, ever seen something you invented echoed back in the world? Something that made you feel like your imagination had cracked reality?

DANIEL HANDLER: I love that story, which embodies exactly the sort of alchemy every writer dreams of--that somewhere, people are taking the stories so seriously that they are manifest in the physical world. This, too, feels very Jewish to me--that something doesn't quite count until it's written down--and it's these sort of stories from readers that feel like a delicious accomplishment. Surely these can count as cracking reality? The deepest and most reliable blessing in my life has been to wander the world sustained by literature, which made me notice things I never would have noticed otherwise. This is the spookiest and most delightful thing in the world.

Oh man. I never really considered what a good interview meant I read til this. So generous on both sides! It’s so clear you’re both really inquisitive kind wicked smart people.

This was so delightful. I came across the interview on Reddit, and I am so happy to have made my way here. I’ve got some wonderful pieces to add to my reading list, and will definitely be coming back to review this when I need some good food for thought.