The following is an excerpt from a forthcoming book by sociologist Frederick Devreese entitled STUDIES IN IDOLATRY: ENCOUNTERS WITH MODERN PRACTITIONERS OF THE SPIRIT DARK (Yale University Press, 2025).

As mentioned in the introduction, the purpose of this book, the driving question, is twofold: 1) to document the various ways that groups of dark practical worship have covertly maintained many of their rituals from Biblical-era origins, and 2) to assert that aspects of their worship transcend the limits of what Borenstein and Barr called “the fabricated non-ritual above movement” into something strikingly affecting and dare I say on the margins of the supernatural.

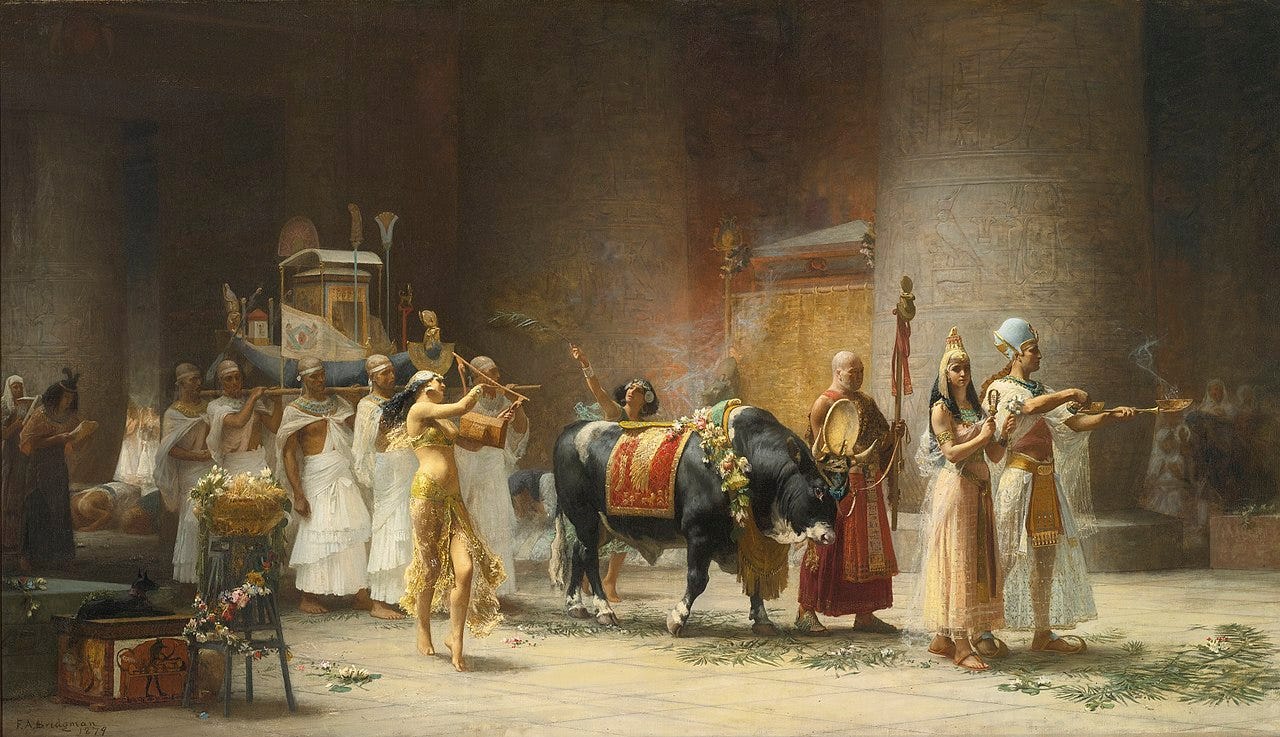

But the true genesis of this book — the product of a decade and a half of dedicated scholarship — is the summation of four separate experiences I had over the course of sixteen months nearly two decades ago. Each of these encounters, from the sleeping handjob soothsayer of New York to the elaborate treehouses of Asheirah, to the fire pits of Ba’al Pe’or, and the near omnipotence of the largest and most powerful order, the so-called “cult of the golden calf,” reinforced the notion that most of the great unexplainable phenomena of life — the cosmochemistry of celestial bodies, the theophanist’s internality, and the chasms of space in between — were believed to be under direct influence of the many “idolatrous” groups of the Late Bronze Age.

The first of these four encounters occurred shortly after I moved to New York to pursue my doctorate under the tutelage of the esteemed Malinora Horssen. While I found her manner and expertise inspiring and catalyzing, I’m ashamed to admit I found a small desk off a corridor in the second largest reading room of Columbia University’s Butler Library even more so. It was here, in a corridor largely neglected due to poor lighting, behind a selection of shelves (HG-18.22 – HU-100.43, Dendrotheology and Arboreal Liturgy) that I spent much of my time, poring over articles and sifting through tome after musty tome, turning pages spotted in yellow-brown, consuming and considering and reviewing and copying down everything I could find related to Asheirah. This was my then driving focus, and still remains an important totem in my work as a scholar. Asheirah, of course, is a West Semitic goddess of fertility as well as an arboreal mother god in ancient Canaanite religion. The Old Testament, in Kings 1-2, tells that she is found both under certain strains of juniper and in wooden items fashioned by human hands.

For a month, two, I plodded steady in my study of ancient Semitic tree goddesses. Other scholars similarly stewed the midnight special, and it was soon common for half a dozen of us to gather on the couches off a second floor lounge at 2 am a few mornings a week, swapping notes and updates over fresh coffee and stale biscottis.

It was here that I first heard of Tembade Henchqueth.

I befriended a budding empathologist at these 2 am nosh-offs who soon became a kind of confidante. It might have been due to her area of study in confessional discourse with a hyper-fixation on disclosure dynamics, but I soon admitted to her my frustration in making little headway in my goal of locating the current whereabouts of the Last Limbs of Asheirah. I’d found reference in many books to this supposed sect existing, and even thriving, somewhere on the continent. Reference, but no explicit mention, which led to lots of recursive searching and double and triple checking.

My friend listened and listened (a true empathologist!), and when I finished, she suggested I pose the question to Tembade Henchqueth. I asked who he was, and she gave me a brief description of his process. It sounded as absurd as it did obscene, but had an intriguing air, the corrective pull that every great scholar recognizes as an essential component of their work.

Which is how I found myself, two weeks later, at an unusual party conducted in a converted gymnasium in downtown Manhattan. The room was filled with people. Chairs faced a stage on which sat a made bed, a stool, and a table. On the table was a pill bottle, a glass of water, and a sleeping eye mask. The chairs were empty. Everyone stood to the side, mingling. Other than the stage, the room was poorly lit, but two figures stood out. A man and a woman, each dressed in silk pajamas and shearling moccasins. An attendee confirmed to me that the man was Henchqueth. When I asked who the woman was, he shrugged and said, “His latest.” For approximately half an hour, I watched people line up to speak briefly to the pajamaed two, and then the lights dimmed.

Everyone in the audience found a seat, including me. Henchqueth ascended the stage. He walked to the table, took a pill from the bottle, downed it with a sip of water, put on the eye mask and climbed into bed. A minute and a half later, his snores were audible.

At this point a voice on the loudspeaker announced, “Palms and fingers in motion of that which will come. Tonight’s role of sacred matron is conducted by” a name I won’t name here. The woman in the pajamas ascended the stage and took a seat on the stool next to the man. His right hand was above the covers and she put a pen in it, with the tip pressed against the page.

And then she put on a glove and reached under the blanket. There was a soft gasp from the audience as she began to masturbate him. “Three questions!” she shouted suddenly. “To start!”

A man two rows ahead of me stood up and shouted, “Which epicenter of refineries will yield the highest returns?” The woman whispered in the sleeping man’s ear, while still stroking him under the blanket, and his right hand started to move. “Next!” she shouted when the writing stopped.

A voice thundered from behind me. “When will I die?” Again, the woman whispered into the sleeping man’s ear, which prompted his hands to write. His snores were loud enough to seem exaggerated, and yet I knew they were not.

At this point, shocked by the absurdity of it, but again claimed by that otherly scholarly feeling, the impulse to act, I rose to my feet and shouted, “Where can I find the Last Limbs of Asheirah?” The woman whispered while keeping her motion on his member consistent, and the hand wrote.

“Three more!” Two others posed their queries before the man started to groan in a manner familiar to everyone in the room and when he slumped back in bed, spent, the woman stood up, removed her glove, and thanked us for coming. “Those who asked questions, come get your answers.” Everyone applauded.

When I went to the stage, I could hear Henchqueth snoring. He didn’t appear to be faking. The woman handed me a small piece of ripped paper. I thanked her and left in a hurry. I didn’t check it until I was in a cab heading uptown. When I did, I saw that the messily scribbled answer to my question encompassed two words and four numbers.

crowsnest tamuz 1118

The next day I did extensive digging into all arbor related entries and pinpointed my focus on Crowsnest Pass, a mountainous municipality in Alberta, Canada. According to a smudged page in an obscure 1958 book called The Tall Sentinels: North American Conservation and Ecology, there was a gathering of Douglas firs on a closed off patch of land that local legends referred to as “the Trees of Tammuz.” Figuring the four numbers to refer to the upcoming date, November 18th, ten days hence, I made arrangements to visit the area. This was difficult, considering its remoteness, but like any good scholar, I was dogged and persistent, and arrived in the area, by some combination of plane, train, and cab, on the evening of the 17th.

Although the patch of land that housed the trees was said to be closed off, I was able to near the source without incident. It seemed the restrictions were relaxed ahead of their ceremony, something I’d read about. I reached the base of a few trees so enormous in circumference it was difficult to determine their number. From hundreds of feet above, I could hear a curious and calamitous commotion. It was clear this was the place. But how to get up there? The trunks before me were bare, no step-ladders, no trap doors, nothing. Ascent into what I believed held the Last Limbs of Asheirah seemed unlikely. And then I heard a sound behind me and five people marauded into view. All wore costumes over their faces, green leafy masks that differed slightly in style and scope.

They were friendly and waved at me. “Where’s your leaf peeper?” One asked. I told them I’d forgotten it and he said not to worry, he had a few extra. “Just in case,” he winked. “It can get wild in there, and sometimes bushes be flying.” The rest of them laughed and I joined in, although I missed the joke. I followed them away from the trunks. About a hundred feet away, we reached a squat redwood. Carved into its base was a design of a charging bull with trees where its horns should be. The man who spoke to me, the apparent leader of the group, knocked on the wood four times, then paused, then knocked four times again, and then it opened, revealing a large hollow enclosure. After the initial shock, I saw it was a kind of rickety wooden elevator, built in the carved-out center of a titanic tree. A rig mechanism like a hand-crank was set into the floor, and once we were all on, the leader of this group slid the door closed and pulled the crank.

We ascended with an initially terrifying jolt but the rest of the ride was smooth. At the top, we exited into a large wooden room, so big it was hard to imagine we were inside a tree. The group I came with grabbed large robes from a corner rack and changed into them. Quite shamelessly, I might add. They shimmied out of their clothing until they stood there, naked, faces covered by the leaf masks. Not wanting to be outed, I did the same, pulling off my clothing and hurriedly donning a long black robe, after which I straightened my face mask.

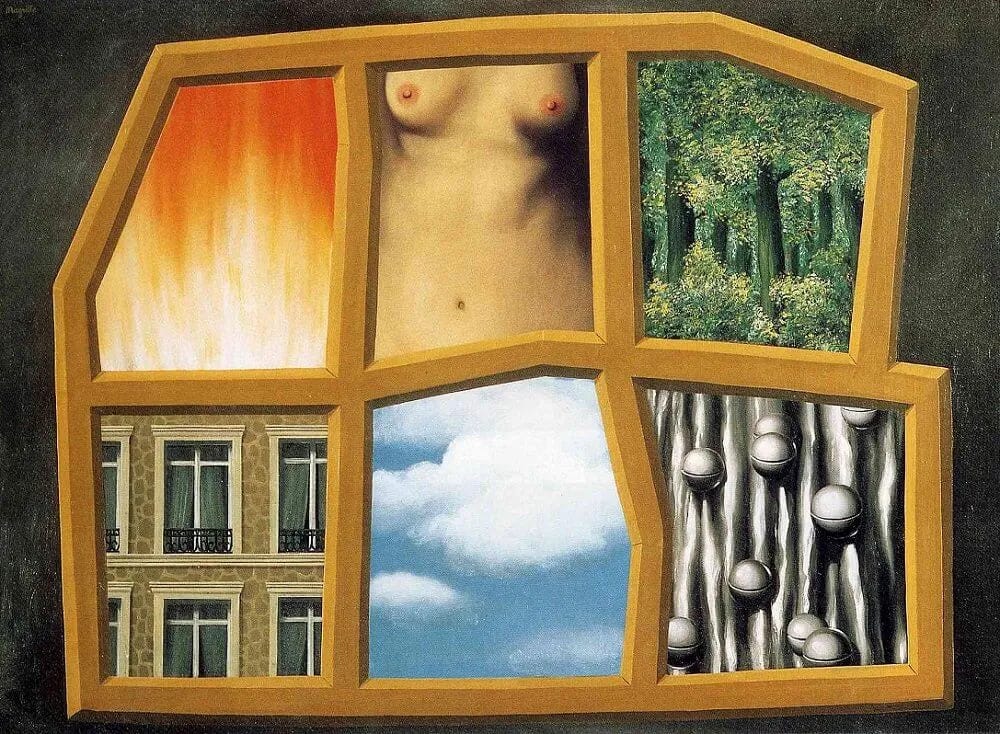

Once we were all robed, we walked to a door at the far end of the room. It was like standing in a crow’s nest above a forest. Before us was a long bridge made of ropes attached to our tree, but also to the neighboring giants. A dozen trees, maybe more, were held together by this extremely complicated system of ropes, pulleys, and precisely placed wooden slats. We walked across the rope bridge, above and through the trees, the din from the gathering growing nearer, until we reached another cavernous indoor platform. Many revelers were here, all wearing the same robes but a variety of masks, most with an arbor theme. There was music, drinks, a staggering buffet of delicacies, including a shrub-themed nyotaimori table, and behind it all, a gigantic wooden door frame, draped in decorative pine leaves.

The leader pointed to it. “That’s where we want to go,” he told me in an undertone. “This is just the antechamber. We want what’s through the evergreen gates. That’s where the freaky deaky happens.” He and his crew headed over there, and of course I followed.

To get through the doors, you had to take a sip from a large wooden goblet. No one seemed curious what was in it. My friend saw my apprehension and told me not to worry. I asked if it was spiked. He grinned. “Sure. Spiked in tree sap.” I took a sip. It tasted like water. To this day, I’m not sure if there was anything in it, or if it was merely a placebo meant to affect the mood. Which it certainly did.

I came into that night hoping to find something usable for my research and came out completely bowled over by the elaborate and seemingly endless treehouses of Asheirah.

I got the gist pretty quickly past the evergreen gates. As a scholar of idolatrous practices of the Late Bronze Age with a specialty in ecological development vis-à-vis latter-form deities, I knew that Asheirah worship was said to be deeply sensual, involving illicit sex, group rites, and even ritual prostitution. However, my theoretical knowledge was poor preparation for what I encountered.

The orgiastic smorgasbord was spread throughout dozens of rooms built on many separate stages of the wooden world above the forest floor. The first few rooms contained furniture on which many people engaged in various forms of fornication. Solo practitioners writhed beside couples across from groups that seemed connected by mouths or groins or chests or hands, a giant heaving mechanical-seeming clash of ecstatically thrusting human bodies. Further rooms past these seemed, bizarrely, designed for groups interested in more specific activities. In one, thirty or so masked men sat while a group of masked women (and men) kneeled before them, fellating with great delight. A similar room for cunnilingus was just past this, and beyond this, the hallway narrowed and ducked off into what seemed like hundreds of passageways, each with smaller rooms in which more precise activities (or the same as those exhibited elsewhere, but in more privacy) were conducted, each with an increasingly clear tree focus.

I saw a room in which phallic pieces of wood were put to creative use, another in which a toweringly tall woman painted to look like an elm stood stoic while others ran around her, caressing different parts of her body, ripe for the grabbing, on each turn, and many others about which I won’t give further detail. Suffice it that whatever you might find on the internet in terms of a pinpointed pornographic preference existed in one room or another of that treehouse.

I wandered around, struck by the brazenness and frequent ugliness of the sights. Maybe it was the sip I took, but I felt strangely detached from myself. I recall being in a large hall seemingly devoted to a network of vines similar to the rope bridge outside, except these were used as sex swings on which couples pivoted and gyrated as they spun. A man in a mask of red cedar caught my eye. Unlike most of those in the room, he was neither participating or staring at those caught up in their passions. He was watching me. I nodded at him and kept moving.

I saw so much, but I did not participate. It’s my belief that an ethical sociologist not only abstains, but abstains with gusto, and yet I admit that my temptation was never tested quite as much as during those forty or so minutes I spent making my way through those rooms, (leaving only when I again caught the man in the red mask staring at me). I tried to find the item I’d encountered in my research on Asheirah, alternatively called the trough, or the rosewood reliquary, or the wooden stunt, but I had no luck. As I discuss later in this book, the trough is meant to capture the semen and saliva of participants as part of an elaborate arboreal fertilization ceremony, birth to the seed of tree and the tree of man, which is the entire point of all of the rampant flagrant sex.

At one point, I found myself turning from the people to the paintings on the wooden walls. One caught my eye. It showed three giant bonfires. Sparking curlicue twists of purple flames. A woman approached me and said, “They’re fun to look at, but truly awful to smell.”

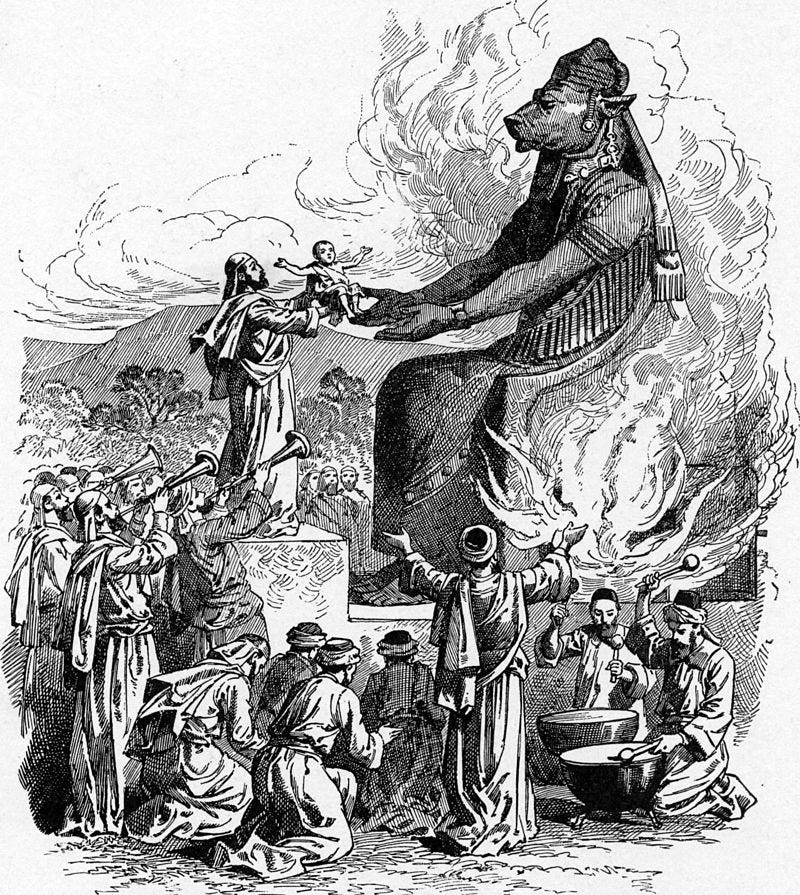

She told me in great detail about the fecally fire pits of Ba’al Pe’or (words that mean, quite literally, “the Lord of the Opening”), which led, nearly fourteen months later, to the encounters I cover at length in the fourth chapter of this book, Excremental Rites, Mud Baptism, Skunk Oil Anointment, and Other Forms of Dirty Worship. My experience near the fire pits left indelible marks on me similar (and yet different) to my experience in the Asheirah treehouse, one for reasons of excessive sexual sightings, the others for the horrid intimations (still unproven) of existent (and even thriving) rites of tophet, or child fire sacrifice.

Then of course, there’s my experience outside the Golden Grounds. I won’t spend too much time on it here, since my sixth and final chapter, The Cult of the Golden Calf: Enshrining the System Built By the Powerful to Serve the Same, deals with just this. It also makes up the bulk of this book, topping out at 111 pages.

All four of these encounters – with Henchqueth, Asheirah, Ba’al Pe’or, and the Goldens – flooded me at moments with a tangible kind of darkness I can’t name, but which lines up nicely with the idea of “kaynóimis,” a well-known mystery word consistently found across various pre-modern worship communities otherwise divided by geography, language, and even vast swaths of time.

In the pages that follow, I discuss the above in more detail as well as focus on the sacrificial farms of the neo-Molochites, the flamebearers of Tar-Amun, and the extant anthropomancists of Amalek. I spill much ink on the Dagon cult, who drink untreated sea water in deference to the giant leviathan they believe reveals itself to them en masse once a year. I recount serpent-swinging with the Nehushtanites, servants of the bronze snake Moses made before Pharoah, later turned into an independent idol of a supposedly profound power.

And so much more. My work is my pride. I hope you find these pages as captivating and enlightening as I found their research.

Frederick Devreese

Delaware

The University of Dover

August 2023