Three Rabbis, or Joseph of the Go-Bells

Nazi ghosts staining a shunted suburban shul

Temple Dark HaMolech worshiped with a holy trinity of rabbis.

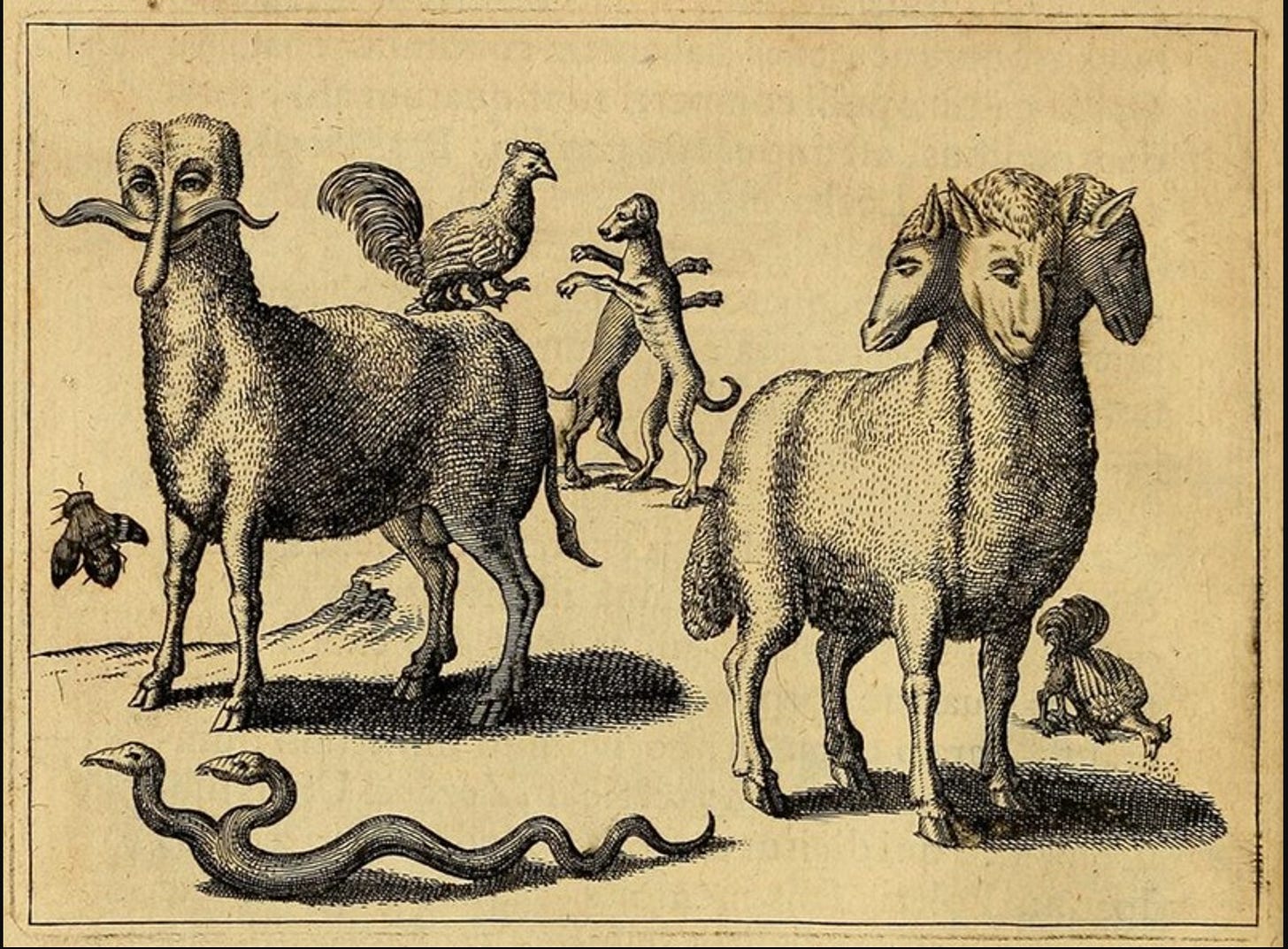

The first was R’ Feldgrau; he was the primary spiritual leader and the youngest by a wide column. He spoke weekly from the pulpit, on Friday afternoons before the shamash lit the Shabbos candles and after prayers the following morning, where he adopted the carriage of a mirth-mired academic in excavating the weekly Torah portion for practical insights and theoretical applications before blessing the wine, the signal for the hot trays of kiddush food to appear, flighty and unseen as if on angel’s wings. New to the role, to the rabbinate, and the spotlit focus of a docile congregation, R’ Feldgrau had much to prove and his speeches were riddled with the crammed-in sources of the insecure. Impressive in scholarship, but built on walls of reed-thin doubt. His was the outermost office in the rabbinical suite – bright windows advertising the holy books and assorted Jewish instruments within, all surrounding a pair of cushy armchairs. His Judaism was the open tent welcome of the first patriarch, and he held no room in his heart for anything closed off and curling away.

R’ Skobeloff, the intermediate rabbi, spoke from his fiberglass shtender once a month, always on the Sabbath afternoon preceding the blessing of the new moon; he was in his sixties and had, for the last third of his life, grown increasingly beholden to the shining shape-shifting orb in the sky. In fact, his office, which was further down the administrative hallway of Todem (a name shaped off the shul’s acronym, TDM), wore windows mostly covered in charcoal sketches of the moon in her various vestiaries, the melon-like curves of waxing crescents, the cover-up of the mesmerizing gibbous on the wane, the full and the empty, here and gone. The Judaism R’ Skobeloff preached was that of Isaac, the second patriarch. It was a strength in silence, accepting the fates of God and of Father, forever willing to go under the knife if the ram was not near. In the vast mind of R’ Skobeloff, this transformed in practice into a kind of selfless devotion, to God and community, to the One Above and also to the Second.

That left the third rabbi, as he was called. In telling, the words came to be capitalized, a totem in Todem of the properness of his noun. The Third Rabbi. R’ Vantaschwartz. The eldest. The one closest to God, then, in years, but also in knowledge.

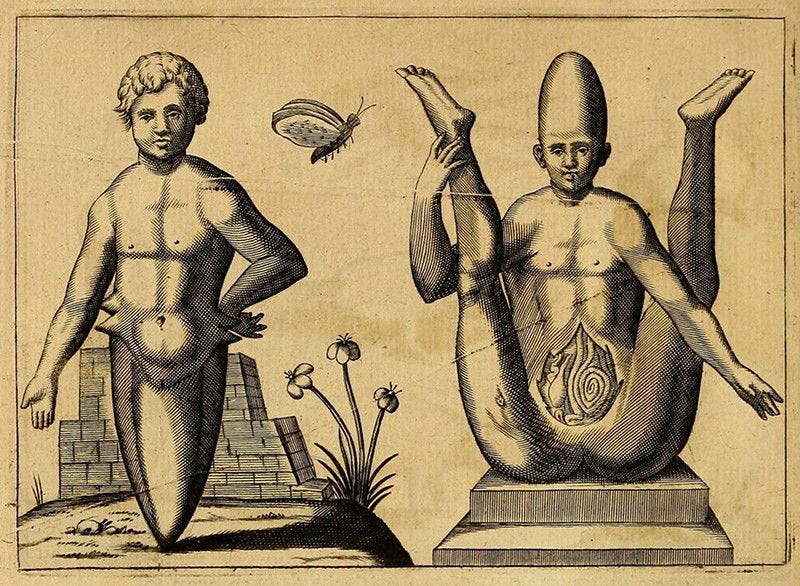

His Judaism, the Judaism of the Third Rabbi, was that of the Third Rise, Third Father, the ever-ascendent transformational properties, Jacob-to-Israel, Joseph-of-the-Go-Bells, the clasp and clench of a human who shared moments of intimacy with the angels, not only grappling but also vision-combing and convers8ing with light. The Third Realm, too, was a part of it. Just check in the many volumes of midrash or the long leather bound mark-ups hidden hard in the Bundesarchiv.

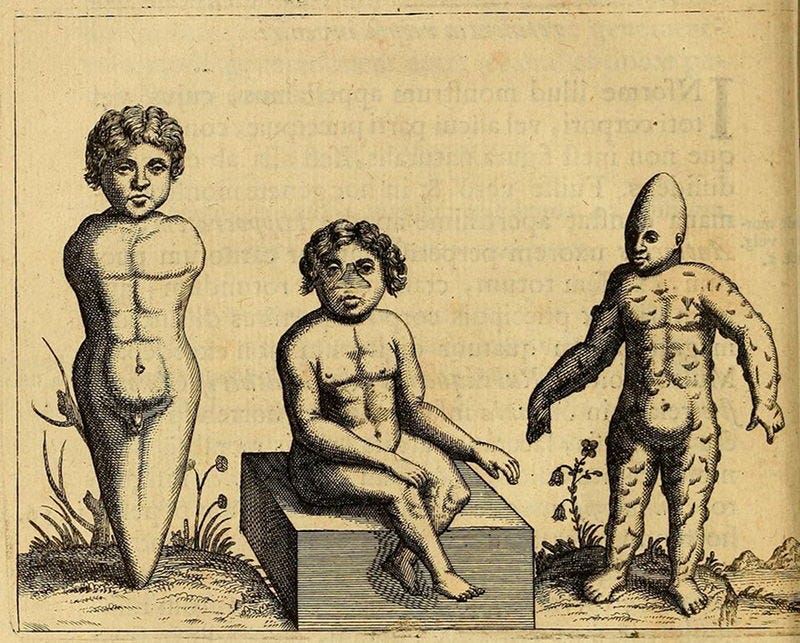

Stories were whispered about the Third Rabbi. He was old, that was the first of it, nearing a hundred, if birth records were to be believed, and given the incredulousness of the stories of his arrival in New York, in the third year of the Nazis’ atrocities against Europe, they weren’t always. The Third Rabbi rarely left his office, which increased the chatter about him: it was no surprise that the specter was improved with absence. He was drawn out by the prospect of rebirth, spring soil, and Shabbos afternoon mincha, the only times he ventured from his office, with its attached bedroom suite in the back, its own private garden behind the gate of the synagogue’s grander garden, a single apple tree planted purposely and perfectly in the center.

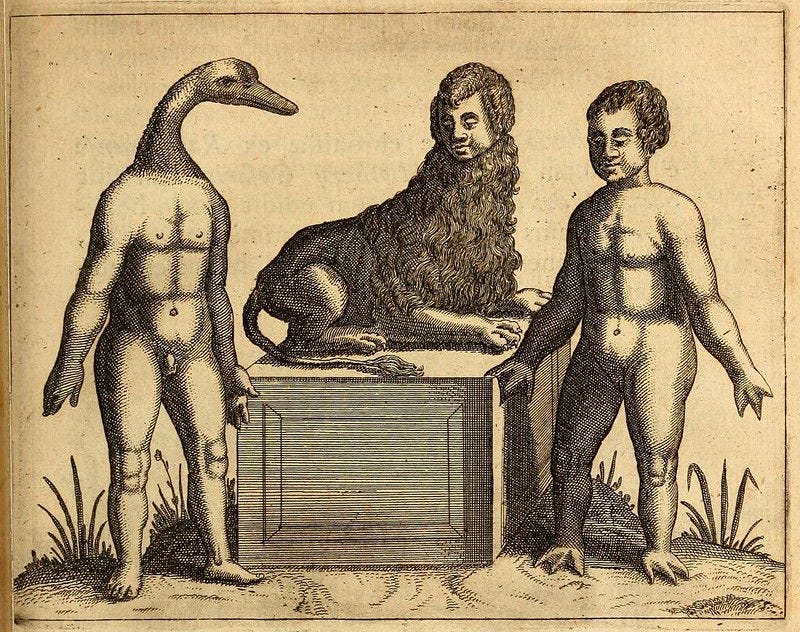

The only time access was granted to the chamber of the Third Rabbi, the innermost sanctum, was for engaged couples the Friday before their wedding.

He gave them a blessing, offered each a shot of whiskey and an apple slice cut from a red orb cropped before their arrival from his hidden side garden. And he then turned to the picture on the corner of the desk. The thought of Joseph. Two Josephs. Joseph in the pit, Joseph in the pendulum.

After the soon-to-be-marrieds left his office, hushed and awed by their exposure to the old man whose hidden ways whispered of the holiness and specialty of the visit, the Third Rabbi removed his glasses, reached into the deepest pocket in his jacket, and removed a small key.

This he inserted into a drawer of his desk by his left ankle, which he opened to reveal a small handkerchief, long faded from its original color. He lifted this piece of cloth, examined it, and said a bracha that most Jews are never even exposed to in the theoretical, let alone find themselves vocalizing ten, twelve times a year. He then pressed the handkerchief to his face so that it covered his eyes, nose, and mouth. And like that, he began to remember.

The Third Rabbi, that stand-in for Jacob, felt most closely aligned with Joseph, the Biblical snake-charmer and dream-weaver, trickster of a Pharoah. The Third Rabbi remembered the things many of his contemporaries strove to forget, if only by their insistence not to look. He looked, only after new love graced his office, because of a line from the Bible, where Joseph names his son Menashe because, “God has made me forget completely my hardship and my parental home.” New love, and the soon arrival of babies to be named, was the balm that let his brain look where his heart (and liver, that spot of mystical existence) would rather not.

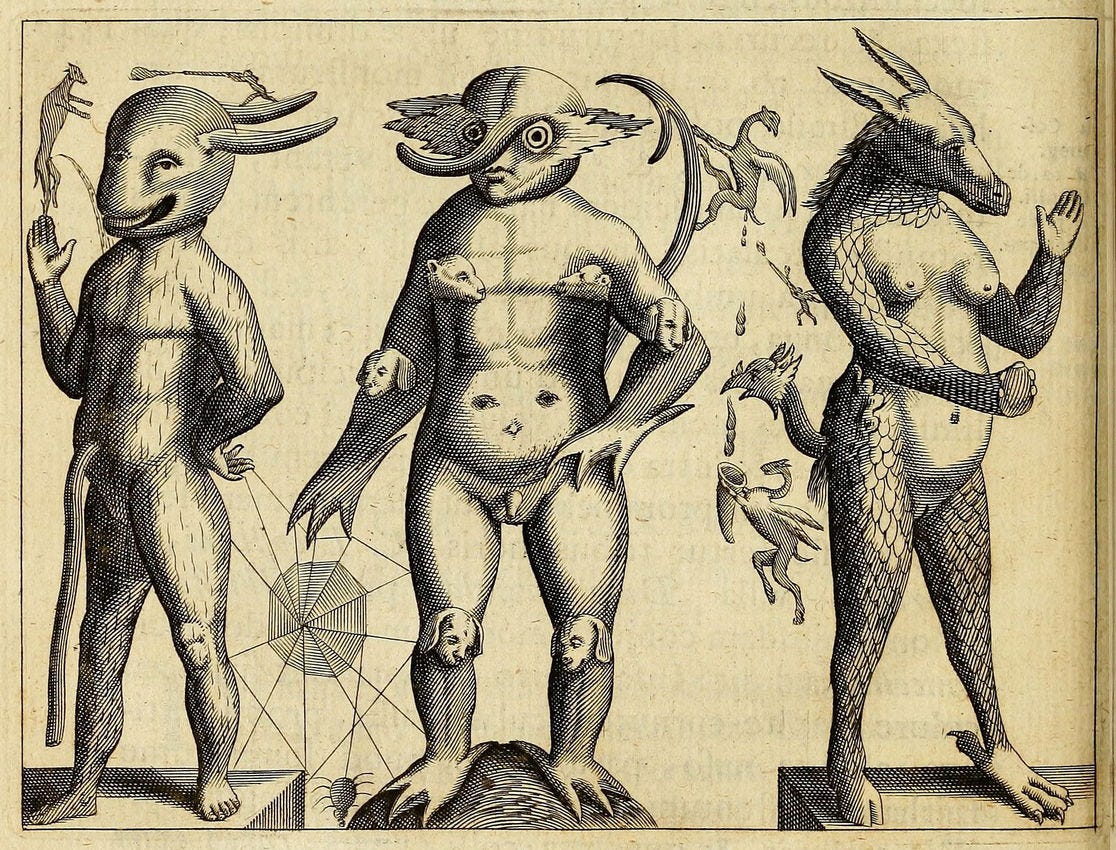

He remembered the atrocities of Germany, after the man with the mustache grabbed the throne (there was none) with an iron grip (his hands were feeble and very human) and turned deep into himself, culling forth the streams and actions of Amalek. Long were the nights the Third Rabbi stayed hidden, first in the forests near his home in the town two hours from Budapest, and then, when the rogues in their military finest marched through the trees, prodding and shooting anyone they encountered on sight, up in the trees, where the leaf cover (unusual for the dead of winter) grew over him and a hearth of some kind — was it the heart of the tree? — kept him warm, against the laws of nature and the reality of the outdoors. Food in the form of small red apples grew from the branches no matter the weather.

And that’s where the Third Rabbi, who was not then yet the Third Rabbi, but something more like a stand-in for Joseph, the good one, encountered Joseph, the bad one.

He was up in the safe haven of his tree when the crunch of footsteps brought him out. Below him he saw the wool tunics, field caps, and dark greatcoats of half a dozen approaching SS soldiers. One stood out. A man in the front with a narrow face, protrusive ears, and not much chin. The Third Rabbi stared at this Third Monster from up in his tree, until the latter seemed to feel the gaze and looked up.

The two Josephs locked eyes. The one on the ground motioned to his sekretärin, but the man didn’t see what was pointed at. The Joseph on the ground stared, removing a handkerchief from his pocket, but the man up in the tree seemed to fade. The lower man heard a tintinnabulation, a pewter ringing far off, and the tree appeared empty. He returned his handkerchief to his pocket, but it fell out and landed on the snowy ground. The Nazis continued their march through the forest. Up in the tree, which was not empty, the Third Rabbi heard the bells and knew he was clinging to something ethereal and other. He scurried down the trunk and recovered the handkerchief on the ground. Inside of it was a single seed, golden and shining.

Years later, and an ocean across the planet, the Jewish Joseph saw a picture of German war-time criminals and recognized the Nazi Joseph. He heard the bells in his ear, fresh like he was back in the branches, and something stirred in him. He took the picture and carried it into his synagogue office. It was there he engaged in study, its light forms and dark mysticism.

New love and lovers, old worlds dying to be together, pits and snakes and dreams away.