The Circumcision: A Story of Shaydim

On blades, blood, babies, and the things that walk like men

Author’s note: The following story reimagines a 300-year-old Jewish folk tale that first appeared in the Kav Hayashar, a work of ethics and mysticism published in Frankfurt in 1705.

I. THE OFFER

Aside from the blood, Steven Messer loved being a mohel. Precision, care, and familial celebration under a veneer of holy initiation. But also, blood. Blood to a mohel was like flour to a baker, especially at the rate of two-to-three circumcisions a week, a schedule Messer had kept for nearly three decades, more than enough experience to never let his disgust show. It was easy enough after the act: stick a wad of gauze soaked in grape juice into a screaming miniature mouth, clean the wound, apply a tiny bandage, and hand the suddenly calm little person back to his parents, a new Jew.

In his fiftieth year of life, Messer had performed over three thousand circumcisions without a single blemish on his record. Judaism — like any belief system based on esoterica it labeled as truth — had many divisions within itself, but none of these mattered to Messer the mohel. He circumcised babies regardless of who their parents were or how they chose to worship, or not. He performed brises for babies born to the pious ultra-Orthodox, where the women weren’t in the room, and for secular Jews whose entire frame of reference were TV shows, where the women ran the room. Even Reform renegades, drawn to his old-fashioned look, sought his services, as did recent converts, LGBT Jews, the post-Modern Orthodox, and so on.

The secret to his success? Ruthie would say it was his halachic training, obsession with cleanliness, and respect for the act. Messer disagreed. He attributed it to the pearl-handled knife he received from his father, the ritual circumciser who taught him everything he knew.

After each circumcision, Messer put away his beloved knife and the rest of the materials in his “brit kit” and rewarded himself. The spread was always impeccable, since this was a celebration and human beings celebrate with food: bagels, schmear, lox, whitefish, tuna salad, egg salad, omelets, noodle kugel, and so on. Plus pastries and cakes as long as the table, and all the coffee and orange juice you could ever want to drink.

One morning, in the third month of Messer’s fiftieth year of life, as he was noshing post-ceremony on a toasted everything bagel with scallion cream cheese, a woman approached him, smiling.

She had a long face and bright eyes and moved with a slight hobble, which reminded Messer of his great aunt Lydia, who had polio as a kid.

“Mazel tov,” he offered the standard greeting. She nodded at him, still smiling.

“You did a wonderful job.” She didn’t blink.

“Thanks.” He debated making his classic bad joke. She looked cheerful, so he thought, what the hell. “Do you want to know the best thing about being a mohel?” Pause. “You get to keep the tips.”

She didn’t laugh, only nodded as if she understood. When she spoke again it was with purpose. “My sister just had a baby. We’re looking for someone to perform the circumcision. We would like it to be you.”

Messer swallowed a bite of bagel and nodded. “Of course, absolutely.” Post-bris schmoozing made up like forty percent of his business. “Do you want my card?”

“No,” the woman said. “We have your information. We have your names. But my community is far away. Across the country. Close to Denver.”

Messer considered. Colorado was indeed a long way off from Washington Heights. “Well that changes things. I tend to stay local. But I can recommend someone by you. I have a friend in Boulder, and he knows just about every—”

“We would like it to be you,” the woman said. Her long face seemed to lengthen and her eyes shone even brighter. She reached into her pocketbook. “We’re ready to pay handsomely.” She handed him a rectangular piece of paper.

Messer stared at the check. It was made out to him and the amount was staggering, simply staggering. He looked at the woman, expecting her to shout “April Fools!” even though that would have made no sense in mid-June.

“Are you kidding me?” he asked. “This is more than I make in a year.”

The smiling woman smiled. “We appreciate you and have been studying you. You’re best for our needs. We’re ready to pay handsomely.”

And when she told him they would also fly him out and put him up, Messer immediately said yes. Being a mohel rarely paid well, and when it did, you ran those checks right to the bank.

II. ARRIVAL AND BIRTH

Two days later, Messer sat in first class, courtesy of his client, looking out the window as his plane peeled off from LaGuardia and took to the skies. Four hours later, it landed in Denver.

The same woman was waiting for him past baggage claim. She held a sign reading MISTER MESSER. On seeing her again, Messer felt a bolt of déjà vu strong enough to alarm him — she was smiling in the exact same manner, eyes glossy and wet, mouth pulled tight, teeth tucked away behind lips — but he brushed it off. He waved at her and headed over.

The smiling woman led him without a word through a door marked Domestic Arrivals. She hobbled to a large black Escalade idling on the curb. A driver stood to the side, and as they approached, he opened the doors, but kept his eyes on the ground.

They drove off in silence, the only sound the crunch of wheels on road.

After twenty minutes speeding down a large highway, the car turned into a tunnel. It was spacious and well-lit, and after a minute, Messer noticed they were the only car in it. They slowed down near a small construction site absent of any workers. The driver got out of the car, moved a few traffic cones, and climbed back in, throwing Messer a nervous look in the rearview. He eased the car slowly through the small site until they reached another opening, a second tunnel presenting as a culvert mouth. They drove through this.

It was darker in this second tunnel, but only for half a minute, because they then breached the surface and were back on a highway under the rising June sun.

Mountains rose in the distance and the sky was blue as sapphire, but with far fewer eyes. Tree stretched their branches to hold the sky in place. The surroundings were so beautiful that Messer didn’t notice they were still the only car.

He checked the time on his phone and was bothered to see he had no service. A nervous feeling settled and Messer stuck his hand in his bag, found his brit kit, and zipped it open. He gripped the handle of his knife, out of sight from the silent woman beside him. Just holding it calmed him down.

They turned off and drove down a side road under stunning Ponderosa pines until they reached the edge of a community. It was surrounded by a large brick wall. Over this, Messer saw the tops of mansions. Many of them.

The car stopped in front of a towering gate, and the smiling woman spoke for the first time since picking up Messer at the airport. “I’ll open it.” She maneuvered out of the car with some difficulty, and hobbled over to a small intercom by the gate. Messer noticed the boots on her feet were large, almost comically oversized.

“Hey!” An urgent whisper.

Messer faced forward. The driver had turned around and was glaring at him. “Excuse me?”

“We only have a second.” The driver’s voice was urgent, afraid. “She’ll be right back. Listen.”

Messer shut up. All five of his senses were suddenly alert.

“These people… they’re different. I don’t know. I’d say more, but—” He looked out the window. The woman had finished inputting the code and was slowly making her way back to the car. “Listen. You’re here. Which is bad enough. But while you’re here, don’t take anything.”

“What do you mean?” Messer asked quickly, quietly. “What is this place?”

“I don’t know,” the man said. “But you got to hear me. You can eat the food, sleep in the beds, bathe in the tub, whatever, but do not take anything. If they even come close to thinking—”

He didn’t finish his sentence because the car door opened and the woman slid back in.

The driver gave Messer a severe look in the mirror and drove through the gate.

The homes in the closed-off community were large and beautiful, done in a variety of stone and brick styles. Each one was bigger than the last, and they drove past increasingly winding driveways and forested front lawns until they reached a pink mansion with three chimneys and enough windows to make an airplane jealous.

Messer followed the woman out of the car. She started walking to the house. With her back turned, he looked at the driver. But the man was too terrified to speak.

This didn’t sit well. Neither did the house. Which was as stunning on the inside as the outside — with all manner of ultra-plush ivory couches, tethered ribcage tables, a ceiling-suspended conversation pit, and long hallways carpeted in gold — and yet something about it had the feeling of a showroom house. Like he was walking through an elaborate staging. People lived there, they had to. And yet it felt to Messer like he was the first person to ever step inside.

This was obviously not true. The woman led him up to a third floor landing, covered in furniture like a hotel, and from there to a small guest room. “Yours,” she said. She told him to leave his furniture, which was strange, until he realized she meant his luggage.

Messer wheeled his roller to the foot of the bed. He reached into his shoulder bag, zipped up his brit kit, and placed it on the duvet cover.

The woman nodded. “Come with me. I want you to meet my sister.” She walked slowly, stiltedly, to a door further down the hall. Smiling at him, that awful unbroken fixture, she turned the door handle and walked in.

He followed her. Inside the room, on a bed large enough for ten, lay an identical version of the woman. Except this one, Messer looked, disbelieving, was massively pregnant.

The pregnant woman smiled at him. She was her twin’s exact reflection, so spot-on it chilled him.

“I want you to meet my sister,” the first one said.

“It’s wonderful to meet you,” the second one said.

Messer didn’t return the compliment. “I don’t understand.” He hated how coarse his voice sounded and how fast the words tumbled out. “The baby isn’t born yet?”

The first one spoke. “He will be.”

“He will be,” the pregnant sister agreed. “Now that you’re here.”

The first sister nodded. She stood at the head of the bed. “Now that you’re here. He’ll be born. Any minute. Come, we must give my sister rest.”

“We must give my sister rest,” the pregnant woman said, which was so jarring that Messer didn’t speak. He just followed his host out of the room.

Back in the hallway, with the door closed behind her, the woman smiled her forever smile at Messer. “The baby will be born tonight. And in eight days you will perform the bris. After that, you may leave.”

He hated how she said it, something obvious that was going to happen just like that. No space for deviation, not a single off-ramp.

She led him back to his room. He asked about the WiFi and when she said “What’s that?” he didn’t detect a hint of joke. That rocked him, badly.

He washed up in a marble bathroom that dwarfed his room, easily twice as large.

Over a delicious dinner that the first sister didn’t touch, his host told him that the father of the child and lord of the manor was out presently but would be back soon. After, Messer retired to his room.

He struggled to sleep that first night, and it wasn’t just the bizarreness of being in a strange place for longer than he planned, with no way to communicate this development to his wife. It was also the screaming. The sister was giving birth in an extremely difficult delivery and her hoarse shrieks were relentless.

But eventually she quieted down, and in the morning, after a few bleary hours of shut eye, there was a loud knock on his door. Messer threw on a shirt. It was the first sister. In her arms she held a baby, her newborn nephew. Its body was wrapped in a silky shawl. The baby’s chest and neck were exposed, but its legs, feet, and head were hidden in the many folds of cloth.

A strange feeling overcame Messer. He didn’t want to, but he was curious. He gestured. “Can I hold him?”

The smiling woman shook her head. “Not until the bris. Have to be safe, you know.”

Messer did not know. “Can I see his little face, at least?”

“You can’t,” she said.

“Why not?”

She gave him a curious smile. “Not until the bris.”

And she carried the baby down the hall and back into his mother’s room.

III. SEVEN DAYS

Stephen Messer’s first day in the community behind the gate was strange. His phone, which had anyway proven useless, died in the afternoon, and there were no outlets anywhere, far as he could see.

He wandered the wishbone-shaped halls of the mansion, trying knobs here and there. Most were locked, but he found a library with thousands of books, a large marble bathroom, and a gargantuan gallery filled with portraits of odd-looking men and women, all smiling, eyes shiny. The full body paintings, and there were a number of them, always ended with the subject’s feet out of frame. He was especially captivated by a portrait in the corner. He had seen it before, he just couldn’t place where. A book? A museum? A previous bris in the home of a different rich family?

The house was so big it had an oversized prayer room in the basement. Messer found this out after lunch, which was conducted back in the dining room. The first sister was there, but she didn’t touch anything. Messer chewed the lettuce and grilled cutlets, unable to overcome his hunger. The food was delicious and the driver’s warning (“Don’t take anything!“) had not extended to it. When he finished eating, a man in large Timberlands cleared his plate. After this, the first sister led him down the stairs.

“This is where you’ll conduct the bris.” She smiled. “In one week.”

It was a nice room. Chairs on either side of a bima, and a standing ark of the covenant in the front of the room, covered by a velvet black curtain. But there was a coldness to the space — maybe it was being underground? — and Messer was glad when she led him back upstairs.

He tried leaving the house, but the weather was bad, rainy and insistent, and with no place to go, there was no reason to get soaked.

So he spent the long afternoon reading in the library. The books were interesting, some classics, but mostly rare first editions he had never heard of. There were books about botany, architectural decay, shadow laws, and forgotten contracts. He read a few pages of a large tome called Thresh-Olds and Other Dol-Mëns: A Top-Ography of For-Bidden Entry before the first sister appeared at his table, suddenly, a cloud across the sun.

“Time for dinner,” she said. But at the table, she didn’t touch her salmon and asparagus and potato soup and cold salad. Messer, who was starving, downed it ravenously. He slept easily that second night, with no birthing screams to distract him.

The second day started out just like the first. Breakfast with a sister who did not break her fast, then a morning in the library. It was less rainy, so Messer went outside around noon to check out the community. Each house was different from its neighbor, equally luxurious and decadent, but uniquely styled. He didn’t see anyone on the walk and when he approached the entrance gate, it wouldn’t open.

Messer tried telling himself that prison, of which he had no experience, was a lot different than this.

On his walk back to the house, he heard voices coming from an external garage. Messer peaked around a corner and saw the driver from the first night.

He was talking to a tall man with bright eyes and the permanent smile that told he was from here. Messer considered getting the driver’s attention, but something about the other man made him want to avoid detection. He watched them for a moment longer and then walked back into the pink house.

After lunch, Messer felt sleepy and retired to his room for a nap. He had changed into shorts and a tee and was about to climb into bed when a knock hit his door.

“Yes?” he said. “Come in.”

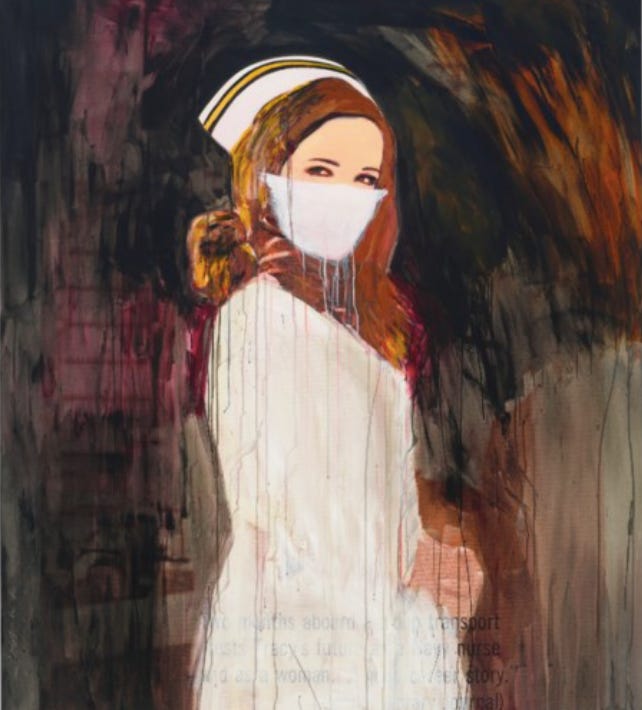

He was expecting the first sister, the only person he’d seen in this house, aside from the mother, baby, and servant in the dining room, and was surprised when a young woman came in, dressed as a nurse.

She smiled at him.

“Um, hi?” Even through his attraction to her, he felt uneasy.

She didn’t speak, just walked up to him, body heaving in her outfit, her feet enclosed in what looked like sacks tied around her ankles.

“What is this?” Messer asked. “I don’t—”

She didn’t speak, just put her hands on his waist and started to kiss him.

Messer recoiled. “What are you doing!? Stop that!”

The woman stopped. She looked at him a moment more, unblinking, and got up. She walked out the door.

Messer was unable to nap after that. All he could think of was Ruthie, the love of his life, and how he had no way to get in touch with her. He held his knife in its bag, thinking of the one he cut for, and the one who just came cutting.

At dinner that night, Messer met the father. It was the tall man who had been with the driver. He was dressed all in black, from his corduroy sports jacket to his pitch pants and the high-shine of his cracked leather shoes. Unlike everyone else, the father seemed somewhat normal. He ate and drank, laughed and cursed, he even blinked and frowned. But something about him combed Messer’s skin worse than the others. It was how he conducted himself, comfortably, like he’d spent time with humans, which is not the same as being them. For the first time since visiting the estate, Messer adopted the veneer of his hosts: smiling non-stop, big and fake.

After dinner, the father shook Messer’s hand and said it was nice to meet him. “I have to travel, but I’ll be back for the bris.” And he was gone.

An hour later, after trying and failing to fall asleep, Messer saw a light through his window. It was coming from the external garage. He watched for fifteen minutes, thinking a wild spread of thoughts, until the light went out.

On his third day there, Messer, bored, took a walk after breakfast through the long empty hallways. He found himself drawn back to the gallery, and especially that one painting in the corner. It showed a big-cheeked young man with dark parted hair staring straight at the viewer. Where had he seen it before? Messer wished he had a working phone.

There was a rustle to the side. A middle-aged woman stood there. Smiling like they did. Eyes shining with the light of something else. Large shoes on her feet.

Messer was caught off guard. He didn’t speak. Instead, he turned to the painting and back to the woman. “Do you know who this is?”

She was silent as she slithered up to him. Just like the nurse girl the other night, she started to kiss him softly.

Messer, shocked and turned on in spite of himself, pushed back. “Stop! What is wrong with you?”

And like a clone of the first temptress, after seeing his aversion, the woman gave him a last look and exited the gallery.

Back in his room, Messer paced the small floor. This was crazy. This was not cool. This felt inescapable. He hadn’t seen a single phone or any kind of modern technology in the house. But there were still so many locked rooms, and so many other rooms he hadn’t even tried. One of them had to have a way out.

A car honk in the distant broke his reverie. He wasn’t totally alone.

Messer left the house. He approached the external garage. The father was gone, but the driver was there, running a rag against the wheels of his car.

“Hi,” Messer said.

The driver immediately tensed. “Are you okay? I wanted to check on you, but I’m not allowed in the house.”

“What’s going on here?” Messer had no time to skirt. “What is this place?”

The driver shrugged. “I don’t know. I got here two days before you.”

“Why did you come here?”

“Same as you. For a job. They offered me a crazy amount of money. Like, obscene.”

“Who are they?”

The driver shrugged. “I don’t know what. They keep it hidden.”

Messer turned his head sharply. “Did you say you’re not allowed into the house?”

The driver nodded. “I was the first night. But then this nurse woman showed up and asked me all these questions, and then they got personal, but I mean, I answered them. I mentioned my scrotal hematoma.” The driver went somewhere, his eyes carrying him off and then back. “They lost interest in me right away.”

“What does that—”

“Hello,” the first sister said. Messer turned. She was standing behind them. “It’s lunch. Come, please.”

Messer, feeling like a kid caught picking his nose, looked at the driver for direction, and finding none, he followed his host back to her home.

The next day, Messer’s fourth in the pink mansion, began with an appearance from the mother and baby. The mother was radiant. In the few days since the birth, she had shed all her baby weight and looked indistinguishable from her twin. The only tell was she was pushed around in a wheelchair and held tight to her hidden baby.

The baby didn’t make a sound. Its face and feet were still covered, but its small belly rose and fell, indicating little lungs at work.

“I want you to meet,” the mother said, although like her sister, she refused to let him hold the child or see its face. “I want you to meet.” It was all she said.

In the afternoon, Messer visited the external garage, hoping to see the driver, but the man was not there, nor was he there later that night, when Messer tried again.

By the end of that long day, Messer understood what the frog in the pot must have felt. An atmosphere presenting as fine but in fact a trap, pointed, turning up, strange and slow, until everything around him was part of the burn.

The fifth day was the strangest. The routine was normal, food, library, art gallery, wander, but after lunch the pot boiled over when Messer visited the garage.

The driver was there, but he was different. He stood straight, much straighter, and smiled at Messer as he approached like he was waiting for him. His smile was the worst, bright and yet dim, an impressive feat, his eyes shiny, much shinier than last time. He no longer wore his open-toed Birkenstocks. Instead he had on big black workboots so large, Messer thought they’d barely fit on a gas pedal.

Messer said hello, but the driver didn’t speak. He just smiled until Messer, spooked out, turned and retraced his steps to the house.

That night, he felt more alone than he’d ever been. He thought of Ruthie, how worried she must be, and how cruel it was — and it was just that, cruelty — for them to keep him here like this, no connection to the outside world. He held his pearl-handled knife for comfort, or was it protection? and fell asleep that way. And the next morning, when he woke up, knife knocked to the floor, he felt lucky he hadn’t cut himself. He returned it to his brit kit and hurried along to the morning.

Day six was soft like sunset, with another avoided seduction (a pretty librarian who had not previously been there), and day seven felt to Messer as silent as the world of Creation before the animals and their noises were birthed into being by the Great Speaking One, Day Four.

Dinner that night was strange. The father was back in attendance, tall and lean and dressed in the same black leather get-up, having returned from his travels in preparation for the bris the next morning, and although he ate and drunk with gusto, he didn’t look once at his guest or his sister-in-law. Nor did he acknowledge his wife and child, who were at the table for the first time, the latter in a crib that obscured him entirely. The father dined in haste and left the room. Silence reigned in his absence. By the time he retired to his room, Messer’s clothing were soaked in sweat.

After dinner, as he prepared for bed, there was a soft rap at his door. Messer was already cautious, and expected either the first sister, which would be fine, or the latest seducer, which was less fine, an ongoing game of this place he did not want to play.

And so when he opened the door and saw that familiar face, it was with shock that sputtered into confusion that soon gave way to joy and full-on embrace.

It was Ruthie.

Messer’s beloved wife stood there, wearing the lace ensemble she put on that one time in the Poconos. Her hair was tied up in the ribbon from their wedding night.

“What? How did you—?”

But then she was kissing him, and it was just like always, so familiar, so wonderful, the same polite highlight of his life, that he went along with it, caught in the unexpected gratitude and joy.

He was so caught in it he didn’t notice the large boots on her feet.

He was so caught in it he didn’t notice her smile was a tad fixed.

He was so caught in it that he barely noticed when she slipped a rubber on him, which wasn’t something Ruthie had ever done before.

It was nice, it was strange, it happened, and it ended.

In the morning, Messer turned over in his bed. No one in it but him. He stretched his limbs, replaying the sexy dream over and over. That’s what it was. Ruthie was not there, nor had she been, although his brain had turned his guilt and genuine want for her into a nice light self-deluding trick.

But this numb illusion was quickly shattered when Messer found a ripped condom wrapper on the floor. It turned sinister after a quick toss and no sign anywhere of the condom. Messer’s heart started to race.

A knock at his door.

“Yes?” he called hoarsely.

“It’s time.” He recognized the first sister’s voice. “Are you ready for the bris?”

IV. THE CIRCUMCISION

Messer clutched his brit kit and followed the smiling woman through the large house. It was empty, as empty as ever of living things, and yet full of material items, pricey furniture and artwork beyond consideration. It was silent, too, although that only lasted until they reached the basement door.

The sound down there was shrill and hollow, repetitive, kind of like the pecking of maddened fowl. But as they descended the steps to the synagogue, the noise shuttered and abruptly stopped.

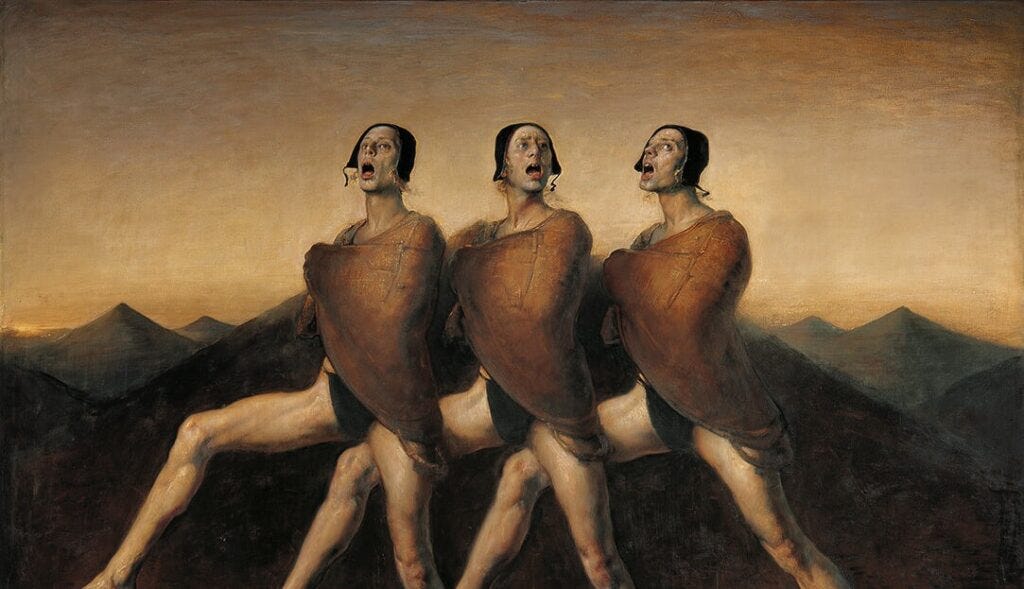

The prayer room was full. Every last seat in the place was occupied. All of them — men, women, boys, and girls — were dressed in their best, in clothing that were fancy in appearance and stitch, if outdated in style. The women wore large hats on their heads and everyone had enormous dress shoes on their feet. All eyes in the room, bright and shiny, followed Messer’s every movement.

In the front stood the bima, short and square. Just past it was the pitch black ark. A structure was off to the side, carved from rough wood, gashed and hammered, the coarsest Chair of Elijah Messer had ever seen.

The father rose to his feet as the mohel reached the bima.

“Please,” the first sister said. Messer turned. She was at his elbow, smiling that terrible smile. “Lead us in the prayer. We can see the sunrise and it looks just like we’ve known.”

Messer felt vacant but did as he was told. He picked up the siddur on the platform. Around him, everyone followed, lifting small identical prayer books. Messer flipped through his and his soul sank in his stomach when he saw that every page was blank.

He swallowed hard, closed his eyes, and lifted the book to his face, creating a separation between him and whatever else was in this room. And when he felt grounded in that separation, and this did not happen immediately, Messer mustered an inner reserve, and it was off this that he recited the Shema from memory, loud and powerful, with as much concentration as he could muster. He felt like he was all alone, braying in a pit for mud to hear him, but he maintained it for as long as he could.

Eventually, Messer opened his eyes, hoping the vocal silence of his surroundings would mean he was the only one in the room, but there they were, all of them, seated, watching eagerly, unblinking. They all held their blank books up to their faces in imitation, but no words issued from their mouths.

The first sister approached. In her arms she held the baby, wrapped in its shawl. Messer took it like a criminal accepting a guilty verdict. The father was already seated in the giant gashed wooden chair. Messer examined the infant. Its entire body was hidden in the folds of cloth.

He lifted the child into the air, said a few Hebrew words, and handed it to its father. Through all this the baby didn’t stir.

The father held the child as Messer rummaged in his brit kit and extracted the pearl-handled knife. He said a few more words in Hebrew and waited for the father to expose the area. There was a quick snip and the circumcision was done.

The baby didn’t cry. Its chest heaved, but it didn’t cry. Instead a sound came from its ribcage — heavy, loud, and slopping, like sea water breaking against the hull of a dark ship. Messer hated it.

The father lifted his newly circumcised child in full view of the congregation. Its face was still hidden but the shawl came loose around its legs, allowing Messer to see its feet for the first time.

They were awful. Ragged, twisted claws curling into themselves — nothing remotely human about them.

“Excuse me.” Messer put his knife back in his kit and hurried from the room. The baby was circumcised, his obligations fulfilled. He hurried up the stairs, attempting via movement to drive the deformed baby from his mind.

Back in his room, he packed up his things and was ready to go in a minute. His plan was to find the driver and get a ride to the airport. If that didn’t work, he’d climb the gate up front. He might not be able to scale it with all of his luggage, but he would gladly abandon everything (except for his brit kit) in the service of just getting away.

He was nearly at the front door when a voice stopped him. “Please. Before you go.”

Messer turned. It was the father. His eyes were large and his mouth was spread wide. He had many rows in there. His son was nowhere in sight.

“Yes?” Messer said.

“Before you go,” the father said, his teeth a rabid pack of wolves. “Please. I want to thank you.”

Messer nodded.

“I want to give you something.”

“That’s okay.” Messer was sweating. “I have to get home to my wife.”

“Of course. And you will. But first, I want to give you something. It’ll take a moment.” He gestured for Messer to follow.

Messer tried telling himself that enslavement, of which he had no experience, was a lot different than this.

It didn’t work. He put down his luggage but took his brit kit with him. Feeling the knife through the cloth made him feel somewhat okay.

He walked after the owner of the manor.

In silence, the two made their way down a long hallway. Messer recognized it from his wanderings. The doors had always been locked. Not so the case now.

The host stopped before the first door and threw it open. “Step inside. Take what you want.” The room was filled with piles of gold, piles and piles of it. Coins and rings and chains and crowns and goblets and helmets and so much more it was astonishing the wooden floor could hold it all.

Messer didn’t enter. “No, no thanks.”

The father gave him a look. “Are you sure?”

Messer assured him he was.

The father led him to the next room. “Step inside. Take what you want.” He opened the door to expose reams and reams of diamonds and rubies, gems and emeralds. Just hundreds of heaping piles of precious stones. It hurt to look at for too long, the crackle in the refracted shine was so blunt, overpowering.

“I’m good,” Messer said, shielding his eyes. “Thanks.”

“Are you sure?” his host asked.

“Yes.”

The tall man led the mohel to the third and largest door in the hallway. “A moment is a lifetime,” he said, and opened it.

Messer gasped. The room was as large as a gymnasium, and it was full of knives. Folding knives, pocket knives, harpoons, hunting carvers, survivalist blades, stainless steel kitchen knives, ancient karambits and ornate daggers, and all kinds of swords. He felt terribly tiny, like a flea staring up the back of a porcupine.

“Step inside,” a voice said.

But Messer had no ear for it. There was one knife in the room, and it was screaming at him. On a table in the center was his knife, the pearl-handled blade he inherited from his father.

Except that was impossible. Messer’s blade was in his brit kit, which was in his hands. Except when he fumbled through the cloth container he found nothing.

“Take what is yours,” the voice demanded.

And when Messer didn’t move, it added, “Go on.” The voice was metal and gold, diamond-hard, cut with the sharp side of a thousand crowns. It made the speaker sound ten feet tall, but Messer didn’t turn, just kept his eyes on his blade.

“Take what is yours. He wants you to.”

It was clear who the voice meant. Next to the blade was the portrait from the art gallery, the painting of the familiar face. Messer stared at his father as a young man, captured in oils and pastels, and entered the room. He took the knife and returned it to his brit kit.

Back in the hall, the man of the manor was smiling, a gracious host once more, beaming at the person who had circumcised his child. He was tall, but nothing exceptional. “That’s settled. You want to leave, you said? I’ll have the car take you to the airport.”

He led the way to the front of the house. Messer noticed he had removed his shoes. His real feet were just like his sons — clawed, mangled, separate.

Messer moved as if through a dream.

The two sisters were waiting by the front door. Their shoes, too, were off. The mother sat in her wheelchair, baby in her arms. Its face was still covered. Ruthie sidled over on large splayed chicken feet. She stared at Messer and made an inhuman sound, her eyes bright enough to burn.

Messer turned from her.

“Please,” the mother said. She held the baby up. “Look, now.”

And she unwrapped the cloth, revealing the baby’s face.

Messer felt a violent wash, something like projectile inebriation.

The child’s face was his own, Messer’s adult face, stretched and pulled taut over a too-tiny skull, distorted by wrenches into a horrible facsimile of a person, himself.

Messer screeched and screeched.

And then the driver was there, leading him from the house, down to the car, where his bags waited him.

Messer the mohel sat in the car, his insides thundering, as it left the gated community and wove through the forest and tunnels leading back to Colorado.

It felt like a piece of him was not returning. A defining part was stuck behind, splayed in the shadows, pecking away, growing in its stilted manner, living a grotesque half-life in the patches of shade (שֵׁד) that exist between the suns (בֵּין הַשְּׁמָשׁוֹת).

״וְהָיָה טַעְמוֹ כְּטַעַם לְשַׁד הַשָּׁמֶן

אִיכָּא דְּאָמְרִי: לְשֵׁד מַמָּשׁ

מָה שֵׁד זֶה מִתְהַפֵּךְ לְכַמָּה גְּווֹנִין

אַף הַמָּן מִתְהַפֵּךְ לְכַמָּה טְעָמִים.״

יומא ע"ה-

Author’s note: Thanks for reading! I love this story, and I plan to turn it into a treatment for a screenplay and then a screenplay. It’m making it my summer writing project, but I’ve never written a screenplay before. If you have any tips for converting a 6,000-word prose story into a 90-page script, please let me know!

It reads like a collaboration between Franz Kafka and Bernard Malamud- which is to say, it's very well done.